Our British rivers and estuaries once teemed with life but much was lost due to pollution and flow restrictions in the 20th century. Thanks to European Union legislation, and the work of many incredible institutions to implement it, these habitats are now vastly improved across much of the British Isles. However, some of the incredible species that once dwelled within our rivers and estuaries were lost and will not naturally recolonise without human intervention.

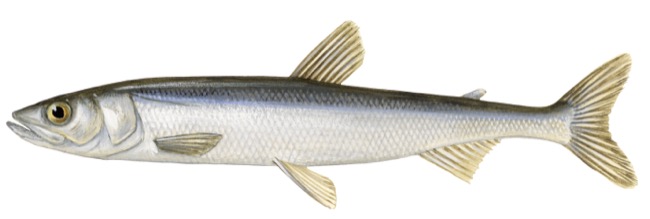

One such species is the European Smelt, Osmerus eperlanus. The European Smelt is an incredible species of fish that is now sadly extinct from many of our river systems. Often called the ‘Cucumber Smelt’ the fish smells incredibly strongly of cucumber and you can often tell when rivers are inhabited by European Smelt by the smell of cucumber emanating from them. This, rather cute looking, fish is relatively small at only about 20-30cm long when fully grown. It is a somewhat pretty fish, with large fins, bright silver scales a often stripes of darker colour running laterally along its dorsal surface. Like Salmon, the European Smelt spends most of its life at sea and only comes into rivers to breed, where it does so on shallow sand banks often many miles upstream. However, quite unlike Salmon the European Smelt does not travel great distances at sea but instead tends to stay local to its native river, often staying close to the river estuary and no more than a few miles along the coast. This is unfortunately the undoing of European Smelt because as various factors, such as pollution (they are very sensitive to water quality), have caused them to become locally extinct from river systems their limited range of travel makes it quite unlikely that a given river should be recolonised by nearby populations should the water quality improve.

This means that it is required that we must step in and re-introduce them from river systems where they have been lost. As female smelt produce around 40,000 eggs in a single spawning event (typically in the cold months of February to March) it might seem simple to take some of these, fertilize them and simply place them in to the rivers where they are missing. Unfortunately, it is not as easy as that as young Smelt are incredibly vulnerable and ideally, they need to be juveniles or sub-adults if they are to stand a chance of forming a viable population.

Recognising this, the European Union funded the SEAFARE project; a part of which was to tackle exactly this problem – how do you grow European Smelt successfully and in sufficient numbers to make a successful re-introduction program viable? I was employed to take on this research at Bangor University in 2011. So, after designing and building a specialist research aquarium that included various experimental tank setups and all the necessary filtration as well as facilities to grow all the necessary live-food for hungry young Smelt, myself and my colleagues set off to Galloway, Scotland, to collect some Smelt eggs on a cold and wintry day. To obtain Smelt eggs our collaborators at the Galloway Fisheries Trust had caught us some Smelt that had come up the river Cree to spawn. In their hatchery we strip-spawned (which involves gentle massage of the abdomen) male and female Smelt to obtain the necessary eggs and sperm. Smelt eggs are incredibly sticky, which enables them to stick to stones in the river and not be washed downstream by the current, and this presents a problem to us in our experiments so we had to wash them in a slight acid bath to remove their ‘stickiness’. When we returned them to Bangor, we made use of them in various experiments to figure out what the best temperature and salinity was for growing them. We established, for the first time ever, just how embryonic Smelt develop and how fast they grow as juveniles. We ascertained such things as when they transition to various food types and the suitability for different tanks. Would you expect, for example, that juvenile smelt fare best when in blacked out tanks? Clear glass tanks make Smelt fearful and they fight currents in keeping to the corners resulting in lost energy reserves; our answer was to use black plastic wrap to cover all of the tanks and thus make them nice and shady for our nervous baby Smelt.

The result of these experiments (and many months of intensive work!) is the recent publication below that details just how to grow Smelt in captivity for conservation purposes. My colleagues, Dr Nick Jones, Dr Ian McCarthy, Dr David Berlinsky and I hope that institutions can use our protocol to begin to reintroduce this amazing fish to places where it has been lost and our rivers can once again smell like cucumber!

Read the publication by clicking on this link below:

I’d like to take this opportunity to thank all the people I worked with on this project but in particular the Principle Scientist and my line manager Dr Ian McCarthy. This was my first employment after graduating from my Master’s degree and it was a fantastic start to my research career.